Cultural Contact: Sharing Artifacts Across the Globe

The Quest Forward Learning Global Learning Program connects Foundation and Exploration students (traditionally freshmen and sophomores) at Quest Forward Academy in Omaha with students at Mtakuja Secondary school in Tanzania. These two groups of students meet virtually and consistently, sharing their work and their cultures, as well as learning how their counterparts use Quest Forward Learning in another part of the world.

The Global Learning Program (GLP) connects the Quest Forward network by bridging the distance between Quest Forward Learning students and mentors in Tanzania with their peers in the United States. By helping to structure their interactions in meaningful ways, the Global Learning Program enables students to collaborate with other students across the world who use the same methodology. Right now, as a mentor in Omaha, I am working with mentors Mussa Challa and Magreth Kitwana from Mtakuja Secondary School in Tanzania to select the course from which our students will complete artifacts. From there, we will share our artifacts via video conference. Students also share one cultural aspect with the other school.

The GLP was also designed to enable Quest Forward Learning students to share their artifacts with students outside of their respective cultures. One of the objectives of Quest Forward Learning is to help students become more informed about global cultures, and why understanding different perspectives is important to study and integrate into their lives. Claire Murray, the implementation manager of the program at Opportunity Education, was asked about its purpose. “The GLP gives students an opportunity to meet students on the other side of the world,” she says, “learning in the same way that they are learning—students who are very different than themselves, but are still engaging with quests, skills, and habits in order to advance in life and school.”

The GLP differs from other programs, such as pen-pals or regularly unstructured video calls. Instead, the GLP aims to help students find new ways of connecting to other educational resources. As Claire explains, “Rather than just hopping on a monthly call for conversation, the GLP sets students up to talk through what they are creating and learning. The goal is to use these interactions as a foundation for collaboration, such as providing feedback on work products and collaborating on quests and projects. The cross-cultural collaboration adds an interesting perspective to a question or problem that we think students could really learn from.” This is an important skill for students to learn, as jobs continue to change and commerce becomes more global. It is important for students to understand others outside of their own community, and to become aware that their personal mores and norms aren’t ubiquitous. The Global Learning Program hopes to open up more collaborative opportunities for students. There will also be opportunities to produce common quests, which will be completed by both schools and then shared via email or video conferencing.

According to Mtakuja mentors Mussa Challa and Magreth Kitwana, “Learners get opportunities to share their artifacts, getting to see how their fellows study, and the nature of their studying environment. The GLP has affected [our] learners greatly in a very positive way. They get to see how the artifacts of their fellows in Omaha are properly kept and well prepared. They took it as a challenge, because some of our students were not taking very good care of their artifacts after creating them. Not only that, but…learners and mentors get an opportunity to speak about social issues through conference calls. The GLP should be a continuous program because of the benefits that the learners are getting from it.”

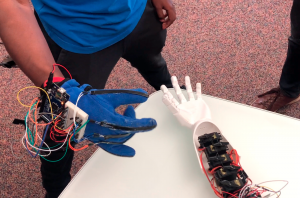

At the last video conference on May 9, students shared artifacts from Science quests. The Omaha students shared a PVC-pipe instrument and a 3D printed hand that was controlled by a wireless glove mechanism. The students in Tanzania then asked questions. The students from Mtakuja students presented a model of a human eye they had constructed. The Omaha students asked how they constructed it, and what resources the Mtakuja students used. The Mtakuja students shared their cultural item: their traditional dress. The Tanzanian boys explained to the Omaha students how you could tell if someone was married or not, depending on the type of garment and the pattern on the material. The students from Omaha were most shocked when an Mtakuja student explained that, in their tribe, boys were not considered men and not allowed to marry until they had killed a lion. The Omaha students did not have a cultural item to present, but instead answered questions about American culture the Tanzanian students posed. The Tanzanian students were surprised to hear that the American students go home every night because Mtakuja is a boarding school, and that in America students eat outside of their homes quite often. The students’ engagement with aspects of each other’s cultures was genuine and full of mutual curiosity. Like all high schoolers, their conversations evolved from awkward moments of silence to lots of laughing, smiling, and explanations for why we do the things we do.