The Elements of Good Game Design Behind Quest Forward Learning

A few months ago, I visited Glasgow Middle School in Fairfax, VA, to see a class of 8th grade students work with Quest Forward Learning. These students work on a quest-based course during their Flexible Instruction Time at the end of most school days. When I asked some of the students for suggestions on improving the Quest! App, they offered a surprising recommendation: “The app is great, but could you add rewards and an in-game currency?”

From this, you would reasonably think that the Quest! app is a game; you would then be surprised to find out that the app enables personalized learning for high school students in academic concepts and skills, and the development of essential life habits. You wouldn’t even be wrong if you looked at the Quest! App as a modern Learning Management System (LMS) for personalized, project-based learning. And yet, I was extremely happy to hear the students’ suggestion, because those students recognized that Quest Forward Learning in general, and the Quest! App in particular, are entirely based on principles that are used in the design of successful games.

In the early days of our work, OE’s CEO Joe Ricketts established “student engagement” as one essential cornerstone for our effort, because he believes that enthusiasm and engaged participation by students in any learning activity would lead to better outcomes than reluctant, bored compliance with the traditional demands of school. Learning science research solidly confirms this perspective.

To understand engagement, we decided to look at “play” – game play, sports, and other activities young adults generally participate in voluntarily with engagement and genuine enthusiasm. More specifically, our research focused on student motivation, the science of learning, as well as principles and game mechanics that contribute to engagement. In other words: Do parents or teachers need to insist that their teenager play more Fortnite and care about it, before going to bed? Unlikely. However, the same usually can’t be said for academic school work.

We participated in relevant conferences: the Games Learning Society conferences, the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco, and the Games for Change Festival in New York. We launched a discovery project with faculty and students of Carnegie Mellon University’s Entertainment Technology Center in Pittsburgh. We collaborated with Fablevision Studios in Boston on early prototypes, to work out how key elements of gameplay would drive learning for students using Quest Forward Learning. Of all the insights that came from this work, one inspiration came from MIT’s Scot Osterweil, who articulates “Four Freedoms of Play”, as essential principles of engaging, effective gameplay experience. These freedoms are:

- The freedom to explore, rather than following a singular, predetermined path or experience

- The freedom to fail, to learn from failure and try again, using failure as a feedback loop rather than a terminal event

- The freedom of identity, enabling gamers to try out various perspectives and roles they might not be able or comfortable to assume in real life

- The freedom of effort, recognizing that total focus and maximum concentration are not possible at all times, and that healthy, productive engagement occurs in organic cycles.

These “freedoms” usually drive well-designed, engaging games that are intrinsically fun to play. Interestingly, both the concept of “freedoms”, and the specific freedoms Osterweil describes, are entirely absent from most traditional academic experiences, and the typical disengagement and boredom with school by teenage learners is an unsurprising result.

So how did we work these principles of engaging gameplay into a learning app like the Quest! App, in a way that would lead the Glasgow Middle School students to recognize them intuitively from their experience with it? A few examples should highlight the point:

- First, we articulated the five Quest Forward Principles that form the foundation of all of our work. They envision students as active drivers of learning (rather than passive recipients), working socially (like in many game and sports experiences) and iteratively (accepting that failure and feedback are part of good games, and part of learning).

- We chose a project-centric approach to learning, and designed “quests” (similar to game-centric missions) as opportunities for active discovery, exploration, and growth.

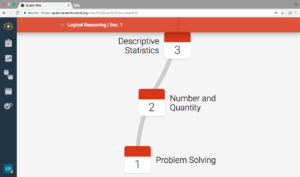

A visual example of the levels students work through during the duration of a course. - Our academic and skills courses use regular language familiar to young adults rather than edu-speak: our courses are structured in “levels” rather than chapters or units, and students work to unlock successive levels by completing quests, much like in many common games.

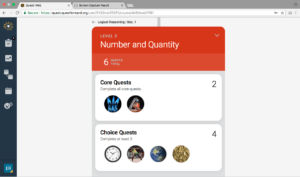

- Each level in a course consists of a few “core quests,” which students must complete to advance, as well as a number of “choice quests,” from which students choose a defined number. This approach ensures understanding of core concepts, and the expression of personal student interest and choice.

- Students work at a personally appropriate pace through each level in the course, rather than following a class-driven, “one-size-fits-all” pace through the material.

- The visual design of the Quest! app was inspired by studying common apps like Spotify, Snapchat, games like Two Dots, the meditation app Headspace, and other popular apps available today.

- Skills and habit development and personal achievements are shown to students in charts and graphs that look more like in-game character attributes than grade reports.

While our Quest! app is not a game, it offers students many of the important qualities of play — agency, independence, personalization, discovery, feedback loops when faced with obstacles or failure, relevance for the student’s life context. The result? Students engage and grow actively; we see them drive their learning and reflecting on their work; they achieving proficiency in given skills in new and better ways; and they express joy in learning, rather than bored compliance.

For young adults today, joyful, engaged, skills-forward learning is essential if we want them to succeed tomorrow.

1. Presentation by Scot Osterweil on the Four Freedoms of Play: http://onlineteachered.mit.edu/files/games-and-learning/week-2/Games-Week%202-Osterweil-as-presented.pdf

2. Video recording of a lecture by Scott Osterweil on the Four Freedoms: https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/comparative-media-studies-writing/cms-611j-creating-video-games-fall-2014/lecture-videos/lecture-15-guest-lecture-scot-osterweil-mit-game-lab/